This week, as I make plans to prepare our traditional Thanksgiving meal for my family, I thought back to the story of the first Thanksgiving. We all have learned that our tradition dates back to the 1621 harvest feast shared by the English colonists and the Wampanoag people – 401 years ago.

But how did they communicate with one another?

I began looking into what happened leading up to that harvest feast. Here are just some of the highlights that I found. The story is actually a fascinating tale.

Pilgrims (1620-1621)

In August 1620, the merchant ships called the Mayflower and the Speedwell set sail from Plymouth, England. Shortly after departure the Speedwell began leaking and both ships returned to port. All 102 passengers were all put on the Mayflower. Because of this delay, the Mayflower had to cross the Atlantic at the height of storm season. As a result, the journey was horribly unpleasant. After sixty-six days, the ship finally reached the New World.

The colonists spent the first winter living onboard the Mayflower. Only 53 passengers and half the crew survived. The Mayflower sailed back to England in April 1621, so the colonists moved ashore and faced even more challenges.

The Pilgrims settled in the abandoned coastal community of Patuxet that had been one of dozens belonging to the Wampanoag Tribe. Four years before, the entire Patuxet community had been killed with the plague that ripped through the Wampanoag nation. It was in these ruins that the Pilgrims began to build their community.

Samoset (1590-1653)

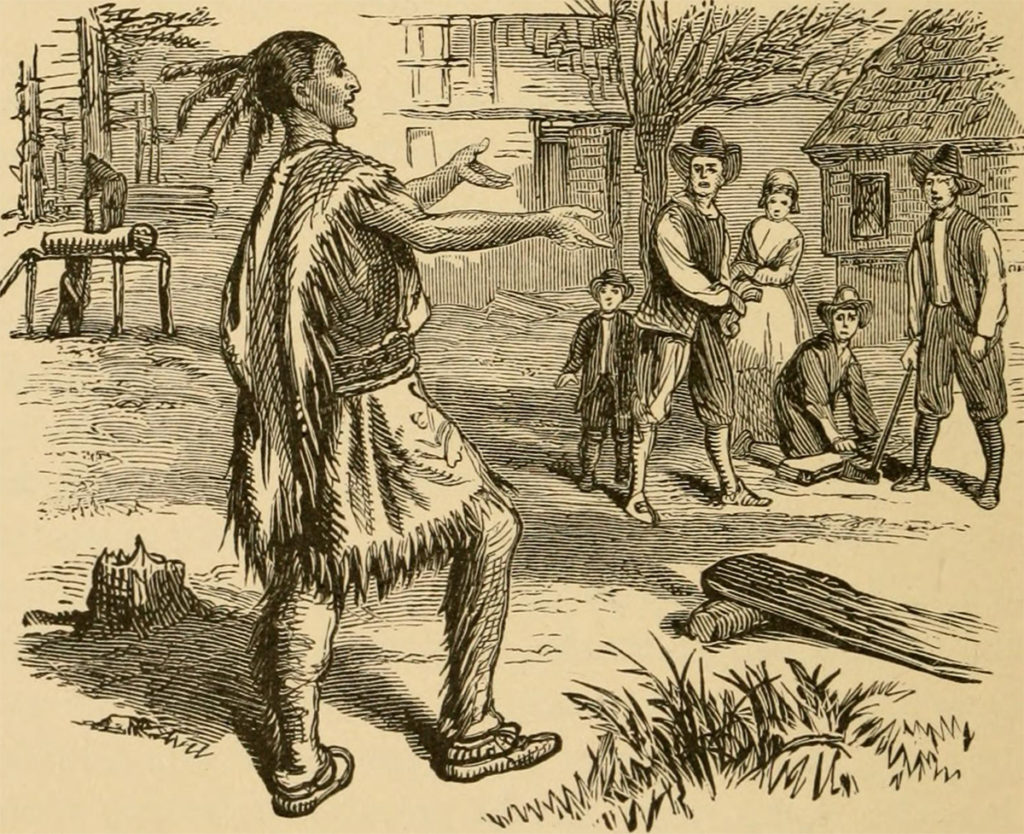

On March 16, 1621 as the colonists were building their new community they were interrupted by an Indian walking directly into their encampment. Samoset walked toward the white men, saluted them, and announced, “Welcome, Englishmen!” in English. Samoset (a sagamore, or lesser chief, of the Abenaki tribe in what is today the state of Maine) was in the Patuxet region visiting his colleague Massasoit, the great Wampanoag chief.

In the area where Samoset lived, he would have had frequent contact with the colonial Englishmen and Frenchmen who vied for fishing and fur rights. Samoset was able to pick up a moderate understanding of the English language.

Samoset introduced the white men to the great Wampanoag chief, Massasoit and his emissary, Squanto.

Massasoit (1581-1661)

Massasoit was the grand sachem (intertribal chief) of all the Wampanoag Indians, who inhabited parts of present Massachusetts and Rhode Island, particularly the coastal regions. In March 1621, Massasoit journeyed to the colony with his colleague Samoset, who had already made friendly overtures to the Pilgrims there.

Convinced of the value of a thriving trade with the newcomers, Massasoit set out to ensure peaceful accord between the races—a peace that lasted as long as he lived. In addition, he and his fellow Indians shared techniques of planting, fishing, and cooking that were essential to the settlers’ survival in the wilderness.

When Massasoit became dangerously ill in the winter of 1623, he was nursed back to health by the grateful Pilgrims. The colonial leader, Governor Edward Winslow, was said to have traveled several miles through the snow to deliver nourishing broth to the chief.

Squanto (1585-1622)

Squanto, a Patuxet Indian, is believed to have been captured as a young man along the Maine coast in 1605 by Captain George Weymouth. Weymouth brought Squanto to England, where Squanto lived with Ferdinando Gorges (owner of Plymouth Company and Weymouth’s financial backer). Gorges taught Squanto English and hired him to be an interpreter and guide.

Now fluent in English, Squanto returned to his homeland in 1614 with English explorer John Smith, possibly acting as a guide, but was captured again by another British explorer, Thomas Hunt, and sold into slavery in Spain. Squanto escaped, lived with monks for a few years.

Squanto eventually returned to North America in 1619, only to find his entire family and the entire Patuxet tribe had perished from the plague. He went to live with the nearby Wampanoags. In 1621, Squanto acted as an interpreter between Pilgrims and Wampanoag Chief Massasoit. In the fall of 1621, the Pilgrims and Wampanoags celebrated the first Thanksgiving after reaping a successful crop. The following year, Squanto deepened the Pilgrims’ trust by helping them find a lost boy, and assisted them with planting and fishing.

Squanto’s unique knowledge of the English language and English ways gave him power. He sought to increase his status among other native groups by exaggerating his influence with the colonists and even going so far as to tell them that if they didn’t do what he wanted, he could have the English release the plague, which he claimed they were holding in storage pits.

First Thanksgiving

Although our Thanksgiving Day is celebrated on the fourth Thursday of November, the first Thanksgiving was not. That feast was probably held between September and November of 1621. The celebration took place for three days and included recreational activities. Here is an account of the attendees:

4 MARRIED WOMEN: Eleanor Billington, Mary Brewster, Elizabeth Hopkins, Susanna White Winslow.

5 ADOLESCENT GIRLS: Mary Chilton (14), Constance Hopkins (13 or 14), Priscilla Mullins (19), Elizabeth Tilley (14 or15) and Dorothy, the Carver’s unnamed maidservant, perhaps 18 or 19.

9 ADOLESCENT BOYS: Francis & John Billington, John Cooke, John Crackston, Samuel Fuller (2d), Giles Hopkins, William Latham, Joseph Rogers, Henry Samson.

13 YOUNG CHILDREN: Bartholomew, Mary & Remember Allerton, Love & Wrestling Brewster, Humility Cooper, Samuel Eaton, Damaris & Oceanus Hopkins, Desire Minter, Richard More, Resolved & Peregrine White.

22 MEN: John Alden, Isaac Allerton, John Billington, William Bradford, William Brewster, Peter Brown, Francis Cooke, Edward Doty, Francis Eaton, [first name unknown] Ely, Samuel Fuller, Richard Gardiner, John Goodman, Stephen Hopkins, John Howland, Edward Lester, George Soule, Myles Standish, William Trevor, Richard Warren, Edward Winslow, Gilbert Winslow.

WAMPANOAGS: There were at least twice as many Native Americans as there were Pilgrims. Edward Winslow’s first hand account in “Mourt’s Relation” states: “…many of the Indians coming amongst us, and amongst the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five Deer, which they brought to the Plantation and bestowed on our Governor, and upon the Captain and others.”