By 1765 John Adams’s legal career was on the rise, and he had become a visible member of the resistance movement that questioned English Parliament’s right to tax the American colonies. He became a leading figure in the opposition to the Townshend Acts (1767), which imposed duties on imported commodities (i.e., glass, lead, paper, paint, and tea).

Despite his hostility toward the British government, in 1770 Adams agreed to defend the British soldiers who had fired on a Boston crowd in what became known as the Boston Massacre. His insistence on upholding the legal rights of the soldiers, who in fact had been provoked, made him temporarily unpopular but also marked him as one of the most principled radicals in the burgeoning movement for American independence. He had a penchant for doing the right thing, most especially when it made him unpopular.

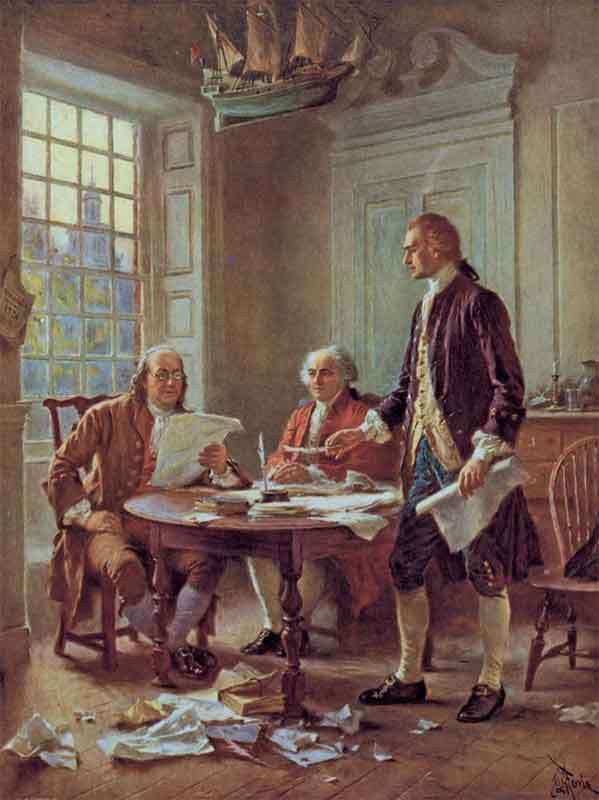

In the summer of 1774, John Adams was elected to the Massachusetts delegation to the First Continental Congress. He quickly became one of the leaders of the radical faction, which rejected the prospects for reconciliation with Britain. By 1775, Adams had gained the reputation as “the Atlas of Independence.” He dominated the debate in the Congress on July 2–4, 1776, defending Jefferson’s draft of the declaration and demanding unanimous support for a decisive break with Great Britain.

On July 2, 1776, the Continental Congress voted in favor of declaring independence from Great Britain. The Declaration of Independence was officially adopted two days later, marked by the ringing of the Liberty Bell at Independence Hall in Philadelphia.

Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson discussing a draft of the Declaration of Independence, 1776

Today’s July 4 festivities would look familiar to Adams. He called for people to celebrate the day with

“Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.”