I don’t know about you, but every time we have to change our clocks, I grumble to myself (OK, not always just to myself!) about why can’t we just leave it on the REAL time.

When I ran across this article in the Saratoga Today Newspaper, it put a new light on “real” time for me. So, I thought I would share it with you.

High Noon

Local time once was set by the noon mark. Noon was defined to be the time at which the sun was directly overhead. This meant, for every approximately 69 miles travelled west, the moment of noon differed by four minutes. For example, the clocks in Boston were set about three minutes ahead of clocks in Worcester, MA.

For example, the clocks in Boston were set about three minutes ahead of clocks in Worcester, MA. This was all well and good, so long as one never left home, or only travelled north and south. When the idea of long-distance travel became more accessible with the advent of the railroads, defining time by “high noon” became problematic.

Railroads

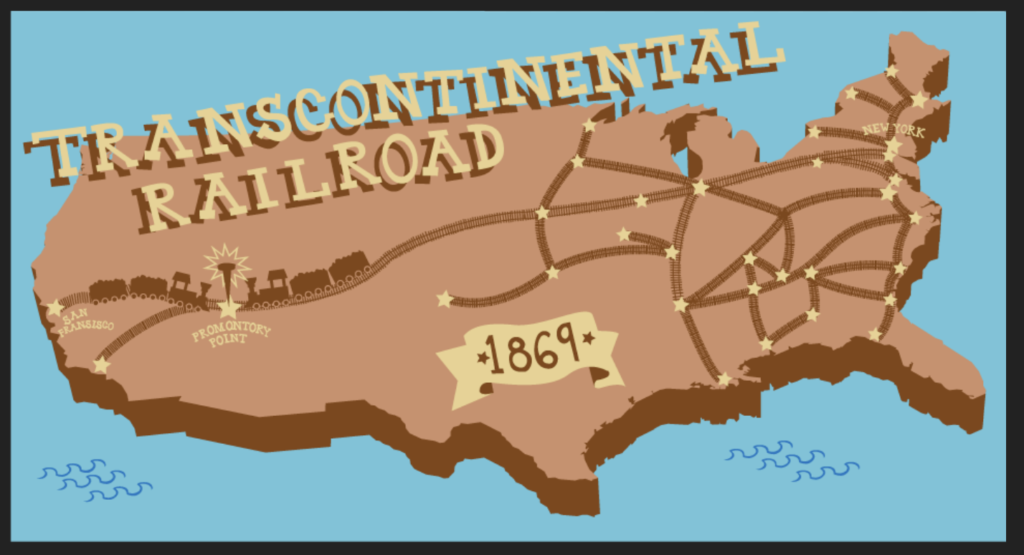

On May 10, 1869, the era of trans-continental rail travel across the United States officially began. But did the trains run on time then? And if they did, who was to say, because whose time did they run on?

By 1879, there were about 500 railroad companies through the country. These companies defined their own time system, based on the local time of one of the cities in their region. To travel just from Portland, Maine, to Buffalo, New York, took passengers through four different time systems. Something had to change.

Father Time (Zones)

In 1868, Charles Ferdinand Dowd, a Yale graduate from Madison, Connecticut, together with his wife, Harriet Miriam North, moved from North Granville to Saratoga Springs where they established the Temple Grove Ladies Seminary. He put his mind to the problem of trains and timetables.

He did consider the uniform national time, as adopted in England, but studying solar times for 8,000 locations across the United States revealed time differences of up to 4 hours, so this was impractical.

National Time

In October 1869, Dowd presented a plan to the Convention of Railroad Superintendents. Following their approval, in 1870, Dowd published a pamphlet entitled “System of National Time for Rail-Roads”. In it he proposed 4 regions across the country, with “Washington Time” the standard time for Atlantic States. (He later modified this to start at the 75th meridian west of Greenwich, to stop arguments over Washington or New York). Similarly, the Mississippi Valley States would be one hour behind Washington Time, Rocky Mountain States two hours behind and Pacific States three hours behind. These divisions were based on approximately 15 degrees of longitude, and within each division, the time would be uniform.

Resistance

Unsurprisingly, there was reluctance to adopt the suggestion. Railway companies and their associated cities were unwilling to cooperate. Albany, New York City and Montreal were only different by a minute, but all insisted on keeping their own times.

13 Years To Implement

Dowd persisted with promoting his ideas. On November 18th, 1883, at 9am, the regulator clock at the Western Union Telegraph System building in New York City was stopped. After precisely three minutes and 58.38 seconds the clock was restarted, and this was the birth of Eastern Standard Time. During the day, a similar event happened at three other locations across the country to start Central, Mountain Standard and Pacific Times.